Are extreme weather events showing up in Australia’s largest city?

Floods and bushfires might affect smaller areas, but droughts, heatwaves, and very heavy rainfall from large weather systems affect large areas. All of the above have occurred near Sydney in the past few years: surely there should be visible signs in temperature and rainfall.

First, rainfall.

In July and October 2022 flooding affected the western Sydney region again, with The Conversation of course saying “climate change is projected to bring far worse extreme rain events than in the past.”

For long term rainfall I look at Sydney’s longest rain records, at Observatory Hill and the Botanic Gardens. Figure 1 shows their location.

Figure 1: Central Sydney, courtesy of Google Maps

Observatory Hill rain records start in July 1858, but the original data ends in August 2020. I choose not to splice data from old and new gauges. Botanic Gardens start in 1885 but there is a large gap, with continuous data from late 1909 to the present. Figures 2 and 3 plot daily rainfall for each:

Figure 2: Observatory Hill daily rain

Figure 3: Botanic Gardens daily rain (1910 to 2022)

Long term means:

Figure 4: 10 year running means of rainfall at Observatory Hill and Botanic Gardens

Note that the means are similar until about 2010 when they start to diverge. Reasons might include changes to the sites. Rainfall was clearly higher in several previous decades.

Figure 5: 10 year running Standard Deviations

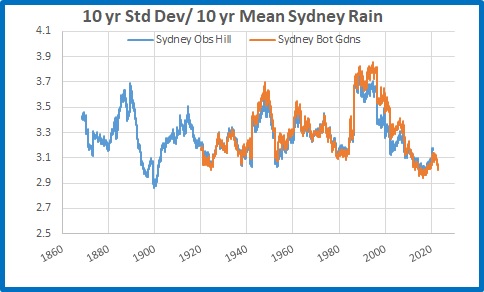

There was much greater variability in Sydney’s rainfall for most of the 50 years from 1950 to 2000. To show Standard Deviation relative to mean rainfall:

Figure 6: 10 year running Standard Deviations divided by 10 year means

Which shows there is little daily variability in rainfall in recent years, and both sites are comparable.

I will now analyse Botanic Gardens data in more detail.

Figure 7: Running 365 day means

2022 was the wettest year on record, followed by 1950.

Rainfall accumulated over several days is a factor in large scale riverine flooding such as occurred in Sydney’s west.

Figure 8: Four day total rainfall

Clearly there were many much greater 4 day rain events in the past than in the latest floods.

I measure “droughts” by counting the number of days with less than 4mm of rain in running 365 day periods.

Figure 9: Running 365 day counts of days with under 4mm of rain

2022 was by far the most consistently wet. There is no sign of increased drought in Sydney.

Conversely, do recent years have more days with high rainfall?

Figure 10: Running 365 day counts of days with over 100mm of rain

No. Only 3 days in 2022, while 1999 had 5, and many others in previous years had more than 2022. It seems that the Sydney region, going by the Botanic Gardens rain gauge, has less extreme rainfall than the past.

I now analyse temperature at Sydney Observatory Hill, using the latest version of Acorn to 2021, and Climate Data Online for 2022 and January 2023 up to Australia Day.

Figure 11: Daily Maxima Sydney Observatory Hill 1910 to 26/1/2023

Maximum temperatures in Sydney, according to the best the Bureau can provide, have warmed at 0.9 degrees Celsius per 100 years. Decadal means show an almost identical trend.

Figure 12: 10 year mean Tmax

Standard Deviation measures daily variability, and 10 year mean Standard Deviations show some interesting patterns:

Figure 13: 10 year running Standard Deviation, Sydney Tmax

Variability is greater with higher temperatures and less with lower temperatures, and temperatures should be related to rainfall- because a dry period will have hotter days and usually cooler nights. Temperature adjustments might interfere with this.

Whatever, there were several past periods with higher Standard Deviations than the past decade, and when divided by the 10 year means the contrast is even greater:

Figure 14: 10 year running Standard Deviations divided by 10 year means

Are days getting hotter? Well, years are, mostly:

Figure 15: 365 day running means of Tmax

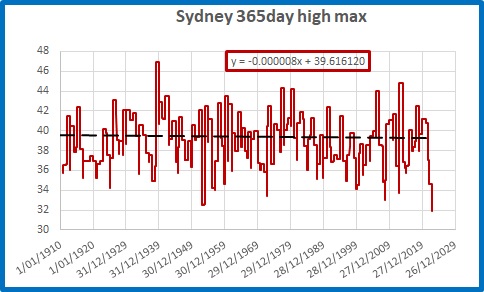

Highest and lowest daily maxima in 365 day periods are not co-operating:

Figure 16: Highest Tmax in 365 day periods

The hottest day was back in 1939, and 2022 had the lowest “hottest day” in a 365 day period on record, with the hottest day being 31.9 degrees.

Figure 17: Lowest Tmax in 365 day periods

Several past winters had cooler maxima.

But is Sydney getting more frequent hot and very hot days?

Figure 18: Running 10 year counts of days over 34.9 degrees

Figure 19: Running 10 year counts of days over 39.9 degrees

The last 10 years have had fewer hot and very hot days than in the past.

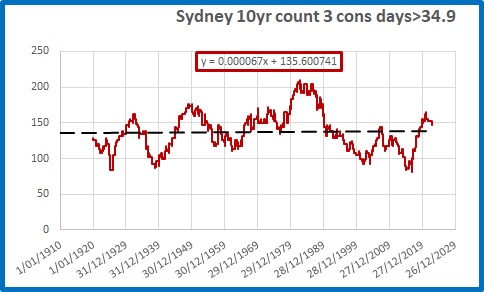

What about heat waves, when there are strings of hot days? The definition appears to have changed, but if we consider three hot days in a row to be a heat wave:

Figure 20: Running 10 year counts of 3 consecutive days over 34.9 degrees

There is a very small trend (0.8 in 100 years) but there were many more 3 day heatwaves in the past.

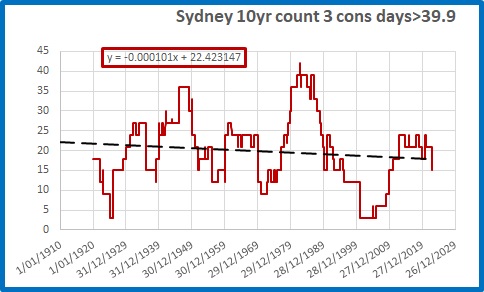

Figure 21: Running 10 year counts of 3 consecutive days over 39.9 degrees

There is a decreasing trend of very hot heat waves (more than 3 less per 100 years), with nearly three times as many 3 day heatwaves of 40 degrees or more in the 10 years to 1982 as in the past 10 years.

Conclusion:

Contrary to popular belief encouraged by politicians and the media, in Australia’s largest city it is clear that:

Rainfall and temperature variability is LOWER than in the past

Droughts are NOT increasing

Extreme rainfall is NOT increasing

Dry years are NOT increasing

Very hot days are DECREASING in frequency

Heatwaves are NOT increasing and are very much LESS COMMON than 40 years ago.

If anything, Sydney’s weather is becoming less extreme and more benign. That should be good news.

We are still waiting for the “projections” of more extreme weather to arrive.