The Australian Greens’ number one aim in their Climate Change and Energy Policy is:

“Net zero or net negative Australian greenhouse gas emissions by no later than 2040.”

And the Lowy Institute believes that Australia can set an example for the rest of the world. In their article ‘An Australian model for the renewable-energy transition’ published on 11 March 2019, they assert that across the world “A very rapid transition to renewables is in process” and that “Most countries can follow the Australian path and transition rapidly to renewables with consequent large avoidance of future greenhouse emissions.”

Time for a reality check.

In this assessment I use energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions data from the 2019 BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

First of all, greenhouse gas emissions. In the BP Review,

…carbon emissions … reflect only those through consumption of oil, gas and coal for combustion related activities, and are based on ‘Default CO2 Emissions Factors for Combustion’ listed by the IPCC in its Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (2006). This does not allow for any carbon that is sequestered, for other sources of carbon emissions, or for emissions of other greenhouse gases. Our data is therefore not comparable to official national emissions data.

Excluded sources would include for example cement production and land clearing. However, given that we are focussing on the transition away from fossil fuels towards renewables, that is not a problem.

Figure 1 shows the growth in carbon dioxide emissions (from fossil fuels) since 1965.

Fig. 1: Global CO2 emissions in millions of Tonnes

The big hitters are China, the USA, and India, who together account for more than half of the world total.

Fig. 2: CO2 emissions by the Big Three and the rest

Note that America’s emissions peaked in 2007 and have since declined. China’s emissions rose rapidly from 2002 to 2013. From a low base, India’s emissions growth rate is practically exponential.

Figure 3 shows how Australia “compares”.

Fig. 3: CO2 emissions by the Big Three and Australia

Australia’s emissions from fossil fuels peaked in 2008.

The BP Review’s CO2 emissions data are based on fossil fuel combustion, so I now look at energy consumption since 1965. Energy units are million tonnes of oil equivalent (MTOE), from the BP Review, “Converted on the basis of thermal equivalence assuming 38% conversion efficiency in a modern thermal power station.”

Fig. 4: Global energy consumption by fuel type in millions of tonnes of oil equivalent

(Note:

Apart from 2009 (the GFC) gas has risen steadily, especially the last five years.

Since the oil shocks of the seventies and early eighties and apart from the GFC, oil has mostly enjoyed a steady rise.

Coal consumption increased rapidly from 2002 to 2013 (mostly due to Chinese expansion) followed by a small decrease to 2016.

Hydro power has seen a steady increase.

Nuclear power peaked in 2006 and declined slightly before increasing over the last six years.

Wind and Solar are in the bottom right hand corner. Both are increasing rapidly but are dwarfed by other forms of energy.)

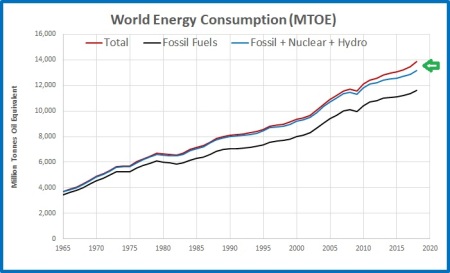

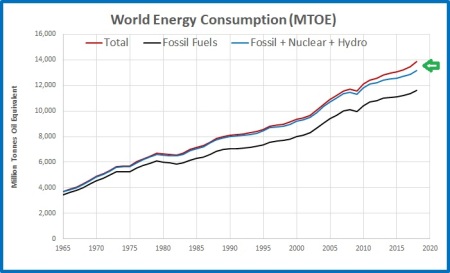

How close are we to the renewable energy transition? Figures 5 to 9 show 1965 – 2018 energy consumption for conventional sources (fossil fuels plus hydro and nuclear) and the total. The gap between conventional and total energy use is filled by renewables OF ALL TYPES- solar, wind, geothermal, bio-waste (e.g. sugar cane bagasse), and bio-mass used for electricity production, (but excluding firewood, charcoal, and dung). I have highlighted the gaps with a little green arrow.

Fig. 5: Total and conventional energy consumption in millions of tonnes of oil equivalent

In 2018, renewables of all types accounted for just 4.05% of the world’s energy, fossil fuels 83.7%. So much for rapid transition to renewables.

The next three plots show energy consumption of the big emitters.

Fig. 6: Total and conventional energy consumption- China

4.38% of Chinese energy came from renewables in 2018. Nuclear and hydro power have increased enormously over the past 15 years and make up 10.35% of usage but fossil fuels (mostly coal) make up 85.3% of energy consumption.

Fig. 7: Total and conventional energy consumption- USA

Renewables accounted for 4.51% of US energy. Fossil fuel and total energy consumption peaked in 2007 but has recently started increasing mostly due to gas and oil use. (Coal has slipped from more than a quarter of the fossil fuel total in 2007 to less than a sixth in 2018.) Fossil fuels make up 84.3% of energy use.

Fig. 8: Total and conventional energy consumption- India

Only 3.4% of India’s energy comes from renewables. India’s energy consumption is growing very rapidly, and 91.6% of consumption is from fossil fuels.

What of Australia, supposedly setting an example for the rest of the world to follow?

Fig. 9: Total and conventional energy consumption- Australia

After years of building solar and wind farms, and at enormous expense, renewable energy of all types accounts for just 5% of Australia’s energy use- and the Greens aim to have zero net emissions in 21 years from now.

In the past 10 years, renewable consumption has increased by 5.5 million tonnes of oil equivalent- but fossil fuels have increased by 6.4 million tonnes. While coal use has dropped by 12 million tonnes, this has been more than replaced by 18.4 million tonnes of oil and gas. That’s not much of a rapid transition.

Figure 10 shows in order renewables consumption in all countries. Remember, this includes all types including geothermal energy and bio-mass.

Fig. 10: Comparative penetration of renewables

Australia at 5 % renewable consumption is 19th and ahead of the big emitters, the USA, China, and India.

Perhaps the Extinction Rebellion activists who are unhappy with lack of action against climate change in Germany, the UK, and Australia, could glue themselves to the roadways in China, India, or Russia.

There is no rapid renewable energy transition. Oil, coal, and gas are cheap and readily available and are powering growth in developing economies. At some time in the future there will not be enough accessible fossil fuel to sustain the world’s economies alone; uranium too will one day be in short supply. However, necessity and technological innovation, not legislation, will drive the adoption of alternative fuels.

Rumours of the imminent death of fossil fuels appear to be greatly exaggerated (with apologies to Mark Twain).